Joyceans and longtime Rosenbach friends are well-acquainted with the history of how James Joyce’s Ulysses ran afoul of the Comstock Law, which prohibited use of the postal service to mail “obscene” literature among other things. The magazine The Little Review, which published the first chapters of Ulysses serially up until the “Nausicaa” episode in 1921, was brought to trial for circulating that controversial chapter; its publishers were found guilty of obscenity and compelled to cease publishing passages from the book. At that time, Ulysses was effectively banned in the United States (both in its serialized form and as the 1922 novel published by Shakespeare and Company) until its case was revisited in 1933. The Rosenbach’s James Joyce collection includes materials from this fascinating history, such as the decision which lifted the ban and a creased 1922 edition that had been mailed to the United States from France in defiance of the ban.

But like its namesake, Ulysses has found itself diverted from its course again and again–in more than one medium!

In 1967, American film director Joseph Strick released a film based on the book. The script, which was almost taken almost verbatim from the novel, earned the film an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. Ironically, fidelity to James Joyce’s own words is precisely what got this film banned in Ireland. Rather than (for example) a cinematic representation of the events that got “Nausicaa” censored, it was the scandalous dialogue that got this film adaptation banned twice—once when it was first released, then again in 1975. The film was only cleared for distribution in Ireland in 2000.

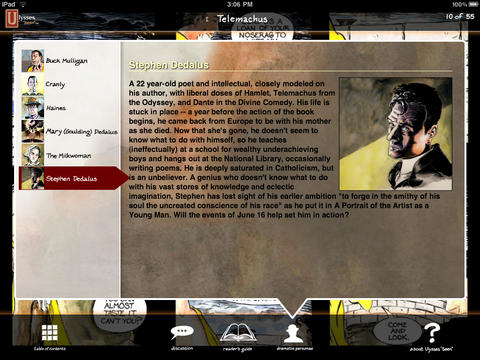

There is, as they say, an app for that: in 2010, the Ulysses “Seen” project released the first chapters of Ulysses on iTunes, with a Reader’s Guide and bold comic-book-style illustrations to help make the novel accessible. But in its early edition, the app included a few illustrations that complemented the novel’s frank, earthy approach to the body–and came up against Apple’s rules against images containing nudity. It’s perhaps a stretch to say that the app was “banned:” it was made available with a few minor changes, such as cropping a female character’s portrait and preserving Buck Mulligan’s modesty, and is still available for download. But this medium makes an unusual addition to the long list of lines Ulysses has crossed.

Why stop there? There is a new “virtual reality” edition of Ulysses in the making, puntastically titled JoyceStick; it will be interesting to see where this interactive experience falls on the x-y axes of “faithful adaptation” and “objectionable content.” And, of course, the annual festivities for Bloomsday that take place all over the world will surely offer opportunities to contemplate what it means for a work of literature to be obscene, or censored, or celebrated. You can join us on Friday, June 16 to have a pint (perhaps in a glass designed by Rob Berry, artist of Ulysses “Seen”) and listen to readings of one of the most famously banned books of all time.